I remember the first time I heard the word ‘rape’.

I was nine-years-old and kneeling on my family’s sitting room floor, rooting through a jigsaw box.

A woman being interviewed by Gay Byrne used it.

Short, sharp and severe.

Without looking up, I asked: ”What’s rape?”

There was a momentary pause before my mother reacted, replying: “It’s when someone has sex with a person, who doesn’t want to take part.”

In a forced act of bravado based on acute embarrassment over my mother’s use of the word ‘sex’, I shrugged my shoulders and replied: “Is that all?”

I don’t recall the moments that followed, or whether there was, perhaps, an exchange of looks between my parents, but I do remember speaking with my mother later that night.

She told me never to dismiss rape. She said she understood my embarrassment, but to respond to rape in the way that I did was wrong.

Given my age, she obviously didn’t intend to have an in-depth discussion with me about it, but it was clear she was desperate to ensure I knew that the severity of the act was not something you could dismiss with a shrug of your shoulders.

At the age of 9, I learned that rape was not something to joke about, or ignore, nor was heartfelt discussion surrounding it something to be embarrassed by.

A year shy of my 10th birthday, I learned that the word ‘rape’ had a profound meaning, that it was a grave matter, and should always be treated as such.

This brief, but poignant conversation contributed to the visceral discomfort I felt years later upon hearing adult peers using the term ‘rape’ in regards to college tests and university exams.

The nonchalant way in which it was flung about unnerved me.

“I RAPED that test,” male students would cheer in the wake of a final exam.

“I was literally raped by that paper”, female peers would mumble.

While arguably a throwaway remark, and not indicative of anything more sinister than linguistic laziness on the part of my generation, it does speak of a more worrying narrative.

And while I can't, hand on heart, say I never fell victim to adolescent idiocy and made a thoughtless reference as part of juvenile discussion, I always, always, always knew it should never be treated with such disregard.

By using the term to describe something innocuous, you essentially reduce the severity of the word and, indeed, the act itself – something which rape survivor, Dominique Meehan, asserted during a recent interview with The Sean O’Rourke Show.

“When I hear a rape joke like ‘My football team Manchester got raped by Chelsea’, that sort of thing, what I hear is that you don’t care about how a rape affects a person. It’s what it comes across as, I don’t care if people don’t mean it,” she said.

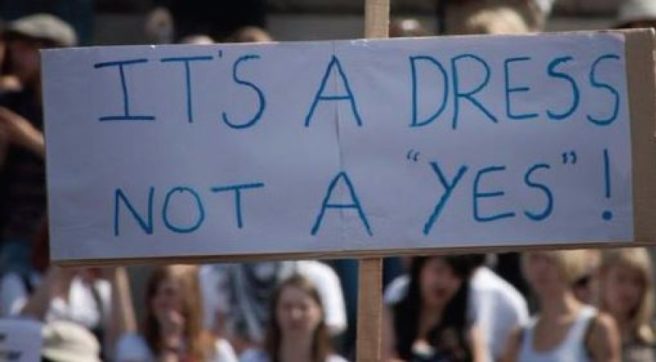

If we’ve learned anything over the years, it’s that rape culture is insidious.

We may not realise we’re contributing to it, but for every time we awkwardly laugh at a slut-shaming remark or merely furrow our brow at a rape joke but choose to say nothing, we’re doing exactly that.

Dismissed as locker room banter when the President of the United States is seen to engage with it, and trivialised when bars and clubs use it to promote their venue, the repugnant narrative that surrounds rape in some sections of society needs further exploration.

And with women like Dominique Meehan calling for it, it’s time we listen, and say no to it.

Short, sharp and severe.