Áine Marry: The Irish artist revealing the truth behind anxiety

Áine Marry is about to graduate from the degree in Painting and Visual Culture from NCAD, and her final exhibition showcases a struggle that many of us are familiar with, but have never been able to externalise.

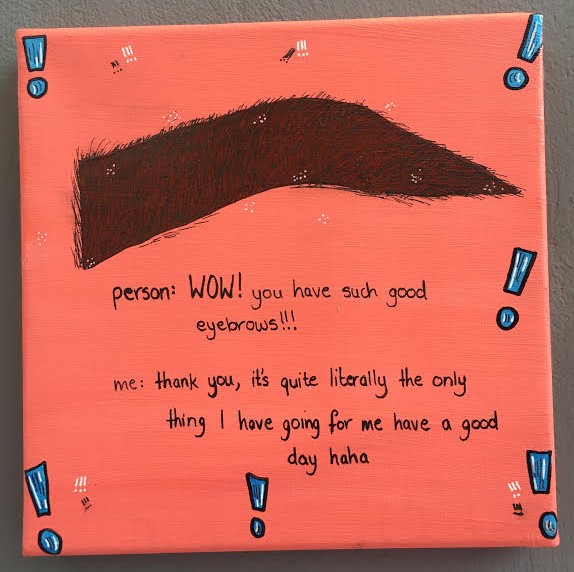

Áine uses her artistic talents to personify the experience of having mental health issues, most prominently, depression and anxiety.

Her exhibition pieces at first glance seem to be bright, cheerful depictions of a yellow-haired cartoon version of Aine, but on closer inspection, the work explores the inner dialogue between the person and the disorder.

Like all the best ideas, the inspiration to begin creating these characters came naturally, from Áine's own experiences with metal health issues, which she feels began around the age of 10 with anxiety.

'They started off as drawings. I had a notebook and it was just a Saturday one day where I hadn't showered and I just literally drew this avatar in a t-shirt and shorts saying 'oh I should probably shower' and I drew another one of this little person in a bed and all of these thoughts about anxiety,' she recalled.

'Once I started posting them to my personal Instagram, people liked it.'

She then brought her paintings in to her tutor at NCAD, who saw the massive potential for development in Áine's concept.

'Then the characters of depression and anxiety, I created them and they started to have a lot more too them, I could put them in different scenarios, like the Tinder profile, I wanted to put them into modern day situations because we live in tis modern social media age.'

Áine's characters live in the digital age, as does her actual art, with an Instagram dedicated to her project which has over 1567 followers to date who follow her process.

Seeing the lives of others through a digitally altered snapshot has become the norm, and while Áine's art Instagram helps others by sharing her relatable work, she feels that the online world can contribute negatively to those who are struggling.

'Before I had my art one [Instagram], I had my personal one, and sometimes you put something up when you don't feel that great, and you feel like you need this response of likes to make you feel better about yourself, like you're worth something, so it can be definitely dangerous.'

'But, it can be helpful,' she said, referencing the more personal pieces of art she has uploaded on her page that she has been wary about sharing.

'They are the ones I get the most response from. I get messages saying 'thank you so much' and it's so worth it then.'

Despite the improving societal attitude sto mental health, Áine still feels there is a way to go when it comes to removing shame from the label

'I still feel stigmatised and I would still squirm while talking about it with maybe family and friends.'

'It hasn't been talked about in so long, and now the conversation has finally been opened and it's stigmatised to a certain extent.'

As a society, the English language has adopted and borrowed terms such as 'depressed,' acting 'bipolar' and 'panic attack ' from the mental health conversation.

This casual use of the terminology, while harmless for the most part, can contribute to the dismissive nature held by some over the struggle of those with the actual disorders.

You know like when you say a word so many times it loses all meaning? It's called semantic satiation and it's a thing, I promise.

'There are people who can't get out of bed for three weeks because they genuinely can't live, where as you have people who are just tired and they're like 'I'm depressed, and that's not to take a way from anyone like you're not allowed to feel that way, but there is definitely people taking advantage of it,' she said, drawing on examples of celebrities using the terms to seem more relatable.

If the term 'I'm depressed' now stands for 'I'm sad,' then how does one with an actual mental health problem describe their symptoms to the wider world without feeling it has been minimised?

Áine's own struggles began when she was a child, but got worse when she transitioned into college life, leading to her seeking help.

'As a young girl it's really easy to start hating yourself visually, I just feel like that's the day and age we live in it's very easy, something can just click in your head where you're like 'I don't look okay,'' she said, reflecting on her relationship with her mental health in her childhood.

'I let myself get really really bad in college, I didn't know if I wanted to be here,' she said.

'You have the core problem but then you have all these other issues that stem from it, so it's been an ongoing thing, but recognising it in college, opening up and talking about it, and being like 'it is what it is' has really helped.'

Áine's exhibition, along with her fellow graduate's work, will be on display on NCAD's campus this weekend.