How does society judge when cosmetic beauty is ‘botched’?

Beauty means something different to everyone. An episode of Sherlock I distinctly remember had the protagonist declare while giving the Best Man’s speech at a wedding; “Beauty is a construct based entirely on childhood impressions, influences and role models.”

At the time, I was roughly 16 years old, obsessed with changing absolutely everything about my appearance. During my school days, everyone wanted to look the same.

The same tanned skin, bright blonde hair which is pretty much only natural if you are of Scandinavian descent, contoured cheekbones and slender figure with a waistline that most likely requires a corset to maintain.

Being different was not only seen as unattractive, it was even feared.

It was only when I entered college and saw beauty expanding its traits that my eyes were opened to different types of aesthetically pleasing looks. As well as this, I began to understand that confidence is beauty.

Happiness is beauty, intelligence is beauty, generosity is beauty. And that beauty is often the least interesting thing about a person.

However, the ideal of beauty which had been prominent during my secondary school years remained the same until the Kardashians exploded onto the reality TV scene, and over the course of the last decade have altered the idea of beauty as we know it.

With their bum and breast implants, nose jobs, cheek implants, lip fillers, whitened teeth among other procedures I don’t have the vocabulary to describe, somehow the idea of what was beautiful drastically changed.

Body modification became far more normalised, as well as the fact that social media gave audiences the power of knowledge.

While celebrities were undoubtedly changing their faces and bodies for decades, especially ones on our cinema and TV screens, social media and the internet now gave us the tools to recognise when ‘work’ had been done.

One fascinating case which has attracted massive public attention in the last few weeks is that of Elliot Joseph Rentz, otherwise known as Alexis Stone.

The make-up and drag artist garnered public furore after revealing a massively drastic surgical transformation to his large social media following, uploading reveal videos to his YouTube channel which were bombarded with negative comments spewing hateful language and even death threats.

Rentz began the process on August 1 of last year, explaining to his following in a video;

“I don’t want to look the way I look today. I don’t connect with what I see. I never have. So I’m changing it all. I’ve been called crazy. I’ve been called botched. I’ve been called an addict. I’ve been called ugly. I’m told every single day that I’ve ruined my face,” he claimed, emphasising that every last cent he owned would be given to his surgical dream of metamorphosis.

“You name it, I’m having it done,” he explained.

Alexis uploads a video titled “The Reveal”, which has since racked up over 450,000 views. In the diary-like visual film, the drag artist shows off his brand new face, which included fat grafts to his nose, forehead, and chin, as well as chin and cheek implants and an eye lift.

“This had nothing to do with vanity and everything to do with sanity,” he quotes, directly from Pete Burns’ biography.

One month later, Rentz uploads a compilation of comments, each more vicious and negative than the next. Some of them are hard to read.

Stone later claimed his so-called friends and family members often joined in on the vitriolic, with some people even telling him to take his own life, and that his ex-boyfriend committed suicide because of Stone.

Roll on January 1 2019, and Stone reveals in a lengthy YouTube documentary that the whole six-month journey was a complete hoax – his new ‘botched’ face was a complex mask.

Working with Academy Award-winning makeup artist David Marti, a stunt mask was even developed from prosthetic facial materials to be worn outside of the house. Months of effort and secrecy had led to this, and the result was fascinating.

He referred to the stunt as a social experiment, while others called it a cry for mental health help, an attention seeking performance or even a show of disrespect for those who have undergone extreme surgery themselves for whatever reason.

So why did he do it, and what did his social experiment show about society’s idea of beautiful versus ‘botched’ surgery?

Ireland’s perception of the cosmetic surgery industry is vastly different from the reality.

NEXT:

Clinics across Ireland have experienced a 75% increase in inquiries about cosmetic surgery; with an increase in both women in their 40's and men choosing injectable treatments.

Those in their 20's are opting for @KylieJenner lips.

Would you consider cosmetic surgery?

— (@BreakfastNT) August 16, 2018

Dozens of clinics have popped up all over the country – Westport in County Mayo is even the predominant creator and exporter of the world’s botox – and yet there is an element of hushed secrecy to the entire organisation.

It is rare to find an Irish person who opens up about having plastic surgery, we are a country of people who lament so-called ‘narcissism’, yet self-confidence issues remain potent within our society.

In a society that profits from self-doubt, liking yourself is an act of rebellion.

In a society that profits from your self doubt, liking yourself is a rebellious act pic.twitter.com/RAqIHtaL0u

— Caroline Caldwell (@DIRT_WORSHIP) May 17, 2015

Jameela Jamil has frequently found herself in the public eye for her scathing indictment of the Kardashian family, arguing that their world is one which 'recycles self-hatred'.

Yet the reality TV clan have essentially transformed the perception of beauty over the last decade, morphing women into self-obsession with curves, plumped up lips, tanned skin and bodycon clothing.

“You’re selling us self-consciousness,” she claims, portraying her deep disappointment of the ‘double-agents to the patriarchy’. Her main issue with the Kardashians is their weight-loss product endorsements, which are basically a fancier packaging for laxatives in protein shake form.

The family have abundant riches which can afford the best photoshop, photographers, airbrushing, personal trainers, stylists, dermatologists and cosmetic surgeons the world can offer.

the kardashian family has created an unrealistic beauty standard through surgery after surgery that women & girls across our country devote their life to recreating in hopes of appearing as what they’ve set as today's social norm. let’s have a conversation about that https://t.co/uMuw8u7VWj

— kelsey nicole. (@kwerdkels) January 7, 2019

Even a glance over websites aimed at young women such as Boohoo, Missguided and PrettyLittleThing shows the huge changes in the beauty industry.

Their models have hyper-miniscule waists and voluptuous curves, glossy brunette locks, tanned skin and full lips, highly reminiscent of the Kardashian family’s idea of what beauty means.

The #10YearChallenge has proven at least one thing; those who have money have a greater control over their appearance than those who don’t.

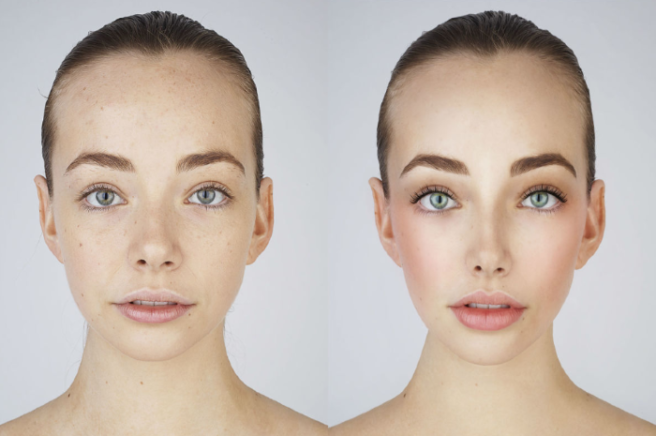

Body modification has become normalised in society, whether it’s permanent or semi-permanent. Contouring, filters on our social media apps, airbrushing, make-up tutorials on YouTube and cosmetic surgery all reflect the culture we live in, which constantly tells us what we look like isn’t enough.

And yet, if a person who changes their appearance is genuinely happier and finds improvement in their mental health and self-esteem as a result of body modification, who are we to judge their lifestyle choices?

Choice is the vital word here. Our society and law consistently shows that it believes it possesses the right to control other people’s bodies. Specifically female bodies.

If another person has the funds and is of sound mind, shouldn’t they be allowed to alter their body if it sparks joy in them, to reference the iconic Marie Kondo?

What struck me most was the understanding which the public has for those undergoing body modification for the sake of their physical health.

Whether it’s a nose job for aiding breathing, a breast reduction surgery to alleviate back pain or even just braces, the level of support appears to be significantly higher when physical health is taken into account, rather than perceived vanity.

Yet if a person’s mental health is suffering as a result of their appearance, is this not still a health reason? On an ‘extreme’ level, is transitioning from a male or female gender to the opposite biological sex classified as body modification?

In this case, a person’s mental health would presumably suffer as a result of their appearance, should they not identify with who they see in the mirror.

Cases of body dysmorphia are higher than ever in Ireland, obsession with one’s flaws can cause great emotional pain. Yet we fixate on the reasoning for a person’s body modification, we presume we have the right to judge them for their choices.

me:

my eating disorders, suicidal tendencies, body dysmorphia, anxiety, anger issues: pic.twitter.com/h0WtMoEVb3— bia (@doceblossom) January 17, 2019

SHEmazing spoke to a young woman named Gráinne, who underwent breast reduction surgery at the age of 19, and never looked back. She was plagued with back pain throughout her secondary school years, but the daily toll which her chest took on her confidence and mental health was the final straw;

“For my own personal experience I would say, I think my chest came in in like first year when I was 13, and got bigger after that. I’d say it probably crossed my mind, a chest reduction every once in a while. You’d be trying on clothes and things just wouldn’t fit, whether it was bikini or swimsuits or whatever, I couldn’t buy clothes that fit. You’d be thinking, ‘just chop them off and be done with it’.”

“Throughout secondary school if you had that idea, you’d just dismiss it, because we don’t do that. I didn’t take it seriously, it was a passing thought. It was first year of college that my cousin, who had a bigger chest than I did, got a breast reduction surgery done. I thought, ‘If she could do it, why can’t I?’ It dispelled the taboo a bit, I guess.”

I'm SO OPEN about my breast reduction. Like I'm sorry if you were around me for 6 months after my surgery because it's literally all I talked about but I don't tell men I had a reduction because so far every comment I've gotten is along the lines of "wHy wOUld YoU dO tHaT?!!1?!"

Gráinne noticed the unspoken way which Irish people often have of burying a topic until somebody else is brave enough to unlock it.

“I hadn’t really thought about it, but that took away the wall up around it. The summer before I started second year in college, it was just getting to me. It affected everything in the way of confidence, everything I wore, playing sports just wasn’t a thing, I just felt vulnerable. My mum always compared it to wild games of tennis at Wimbledon, everything’s going the wrong direction. You’re very self-conscious about it. I was starting to get dints in my shoulders, I would have been 19 at the time so I couldn’t believe I could get them so young”

Gráinne discovered that she qualified for the surgery through the state on medical grounds, and her life greatly changed after that pivotal moment;

“I got my chest done September of 2015, so I would have been 19 when I started. I went to my GP about it, and he referred us. It was on medical grounds, I couldn’t straighten my back or stand for five minutes without a pain in my back because it just couldn’t hold my breasts. You feel like a hunchback all the time because you’re always bending over. I remember when I was going to the consultant, I was more nervous because I thought ‘If he tells me I can’t get this surgery, what am I going to do?’"

"I went in and found out I could have it on health grounds, and I was the right BMI for them to justify it. We had to wait for the insurance to approve it. The only funny thing was that they told me there would be scars. I never cared about this, I knew I could deal with them if it meant that I could have a smaller chest. To this day, I don’t care about the scars. They’re there, they’re fine, they’re healed.”

The process of the surgery itself is a journey, from the initial thought pattern, to the planning, to the operation itself and then recovery. Nobody takes on cosmetic surgery lightly, nobody does it on a whim or doesn’t think it through. They don’t think about ‘ruining’ their looks, or what other people think.

When I got my breast reduction surgery, I wanted my breasts to be as small as possible bc I was tired of the constant back/neck/chest pain and never being able to find shirts that fit me. ALSO because I was tired of men oggling my chest and TOUCHING it without my permission.

— (@juliahagins) January 21, 2019

They have been on their journey for a long time, they are of sound mind, and they have ultimately made a choice and will handle whatever consequences arrive afterwards;

“Having the surgery itself, people would ask me if I was nervous. I kept telling people, ‘Why would I be nervous, I just have to lie there? It’s the doctor’s job.’ I wasn’t nervous, I was excited about it because it meant that so many other things were going to be open to me. When I finally got the surgery done, I was just ready for it. After the surgery, you had to have a week of bedrest to recover, and take care of yourself. It was fine, I had protein and scrambled eggs because the nurses said that it would help the healing of scars. I never put any kind of stress on it, I was always just excited about the chance to have it done. I can’t imagine what my life would be like without having it done, if I was still in the mental headspace of constantly being conscious of my chest like that.”

What changed in Gráinne’s life after her operation, and how does she feel today about it?

“It was just such a thing that you hid before. Everyone in my family had adapted to wearing big jumpers and scarves to hide it, we were a big chested family. I have no problem talking about my surgery, I have no problem talking about my chest size. I was never vulnerable about it, I kind of own it. Every year around the anniversary of my surgery, I think of it like a little victory. It’s an attitude, it’s another year on of not having to deal with my chest. People who knew me and knew how important it was for me were supportive."

"I wonder if there was someone who wanted implants for their chest, would it have been the same reaction? My flat chested friends always joked ‘I’ll use whatever you don’t want!’, I wonder if someone had gotten implants, would it have been the same reaction? Would people have been as supportive? Even if it was for their own mental health because they can’t stand being so flat-chested, I don’t think it would be as accepted.”

Stop shaming women for having cosmetic surgery. Y'all still shame them if they remained flat anyway

I asked Gráinne how her life changed after the surgery, in more than just a physical way;

“It definitely improved my mental health and the way I see myself. It’s made me more accepting of other parts of my body, of me as a whole. My physical health has also improved, I’m more active. I used to do so many after-school activities in primary school, but once my chest developed I stopped those. Sports bras didn’t improve it either. No one in my life ever commented on me having a big chest in a negative way to me, I don’t think. It was just something I wanted.”

Ariel Winter chose to have a breast reduction surgery following years of public and online ridicule, complications involving acting roles as well as intense back pain. Speaking about the difficulties to Glamour in 2015, she said;

“We live in a day and age where everything you do is ridiculed. The Internet bullies are awful. I could post a photo where I feel good, and 500 people will comment about how fat I am and that I am disgusting. On red carpets, I just said to myself, "You have to do your best to look confident and stand up tall, and make yourself look as good as you can in these photos," because everyone is going to see them. I definitely seemed confident; I'm an actress, that's what we do. But on the inside, I wasn't feeling so happy.”

For Gráinne, Ariel Winter’s story deeply resonated with her;

“I saw her on Ellen, and just understood everything she said. You’re so self conscious of it. It would have affected my confidence going on Erasmus, I always hid behind scarves and jumpers. I’m far more confident now, and whether that was just growing up or having my chest done, I feel the chest was a major contributing factor. I’m still a curvaceous figure, but it’s manageable and I’m not weighed down by it. It wasn’t about anyone else, it was about me and no one else. If that’s what someone else wants, then they should go for it.”

When asked her opinion on Alexis Stone’s stunt, Gráinne was struck by the thought of going ‘too far’, and why that seemed to offend so many people. The idea that if you transform yourself to look less like the culturally accepted beauty standards, you are committing a grave sin in some way;

“For the whole Alexis Stone side of things, I think the problem with that was, did he go too far in people’s eyes? He didn’t fit with what society wanted him to look like. Kylie Jenner’s lips, she was self-conscious about them, and had been over-drawing, she got them done, but now we forget that she ever got them done. We accept that this is her face. But with Alexis, everyone thinks he went too far. People getting things like that done are often afraid of other people seeing their insecurities. There’s a model of what society wants people to look like, and you’re either reaching that model or you’re going too far."

"Rachel Green in Friends, it’s so overlooked that she got a nose job, because it was to fix what they saw as a flaw. If Alexis Stone pretended to get work done for what he saw as a flaw, but society didn’t, then it’s a problem. Other people didn’t know about my chest, but I felt that it was a burden for myself and how I viewed myself. It was literally weighing me down. Kylie Jenner’s lips were a flaw to herself, and she ‘fixed’ them and she’s happy. It’s about ‘fixing’ what people’s perception of beauty is.”

What a large group of people perceive to be aesthetically pleasing offers a mirror to that society itself. Sociological factors have a major impact on why we see certain shapes, sizes, faces, skin types, hair and eye colours etc as the desirable way to look. Despite the fact that millions of young women ache to look the same as the Kardashians, it’s what is unique to each person that is the inherently beautiful part of them.

What's 'beautiful' today may be off-brand tomorrow. Why try to keep up?

Today I ask what is beauty? Look how fast it's definition evolves. Examine the never-ending yet ever changing pressures on women to conform. New film by me out today a @CNN commission. HAPPY INTERNATIONAL WOMEN'S DAY 2018 PEOPLE #IWD2018 #IWD #whatisbeauty pic.twitter.com/YT7M5yvGoJ

— Anna Ginsburg (@annaginsburg) March 8, 2018

As well as their appearance, their worth is so much more than what they look like or what they way. What they feel, what they offer to the world, their identities, their language, their flaws, their intelligence, their kindness; these factors are often greatly impacted by appearance, but beauty is more to do with the mind than what the eye envisions.

“Society has an issue with it if it’s pointing out flaws that they see in themselves as well. If you see something that you really admire in someone else, you feel self-conscious about it yourself in some way.”